Estimating Custom Cabinetry Part 1: Introduction to Components, Assemblies, and O&P

Estimating custom cabinets is a time consuming process. After trying many different approaches, I keep coming back to unit cost estimating. It’s the most accurate, most scalable, and is the easiest approach to weed out “holes in your canoe” like a 6-drawer base cabinet when you’re estimating by the linear foot, or a 48” wide wall cabinet when you’re estimating by the box. What linear foot pricing is attempting to do is what I'll be doing here, but in a more precise and scalable way: creating units for quickly and accurately estimating custom cabinetry.

Everything is a unit, but just like how we don't measure water in pounds or bricks by the gallon, you need to use the right base units to have something useful to work with.

For estimating cabinetry, everything will either be by the linear foot (LF), square foot (SF), cubic foot (CF), each (EA), or labor hour (LH).

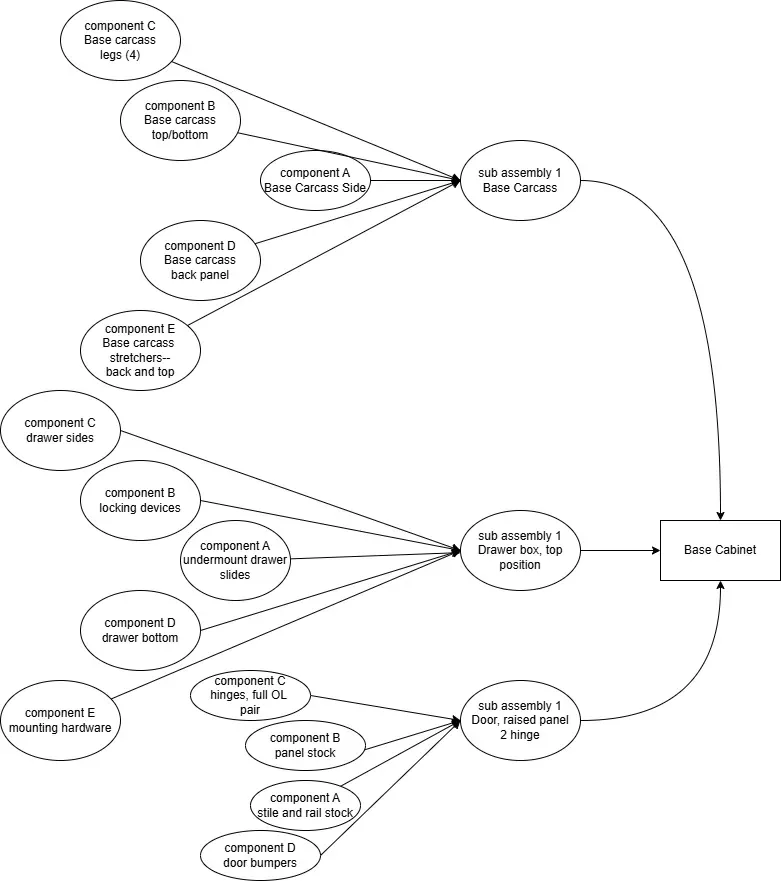

When I talk about unit based estimating, the units are calculated from assemblies.

- Assemblies are made up of sub-assemblies.

- Sub-assemblies are made up of components.

- Components are made from (a) raw material inputs and (b) labor inputs.

For example, a base cabinet with a drawer on top and a door on bottom is an assembly. Its sub-assemblies are:

- Drawer front

- Door

- Carcass

- Drawer

The components that go into each sub-assembly become tedious quickly, but let's do one together. For a drawer, the components are:

- drawer sides

- drawer front and back

- drawer bottom

- drawer slides

- locking devices

- mounting hardware

The raw material for a drawer side is 4/4 maple lumber. The labor inputs are:

- picking up lumber

- jointing

- planing

- setting a dado stack

- grooving for a bottom

When you add a new assembly to your product offerings, set aside time to calculate all these units. It's time consuming, but then you only have to do it once. Here I will lay out the process by which I calculate the unit cost of assemblies. Let's start by looking at the material inputs for each assembly.

Cost-of-Goods-Sold (COGS):

- Your COGS is calculated by:

starting inventory + purchases - ending inventory

Essentially this is everything you have to purchase to produce your project. This is all of your lumber that you have on hand, lumber that you purchase, minus what you have left over to use on the next job. For many shops operating in the lean philosophy, you probably won't have nearly any inventory inputs or inventory remaining by design. For more traditional shops, you probably keep piles of your most commonly-used materials on hand ready to pull from. Your COGS also includes labor that is directly tied to production, such as production worker wages.

I calculate installation labor separately to keep things simpler. There are many more variables that go into estimating field work that are not accurately accounted for in the production of a part in a controlled setting.

Example of Unit Cost Breakdown

Let's calculate the bare cost of a component:

If you're producing a panel product that is 1’x1’ that’s 1/32 of the panel if you get 100% yield. For simplicity's sake I'm not including the "kerf waste" which reduces yield each time a panel is cut.

If you only get an 80% yield, multiply your square feet (32) by .80, giving you 25.6 square feet that you can actually sell of that panel.

If the panel costs $ 100, divide $ 100 by 25.6, multiply by the sf of the component, and that’s your material input. $ 3.91 per component.

You could also increase accuracy by adding in the cost of processing the waste produced if your volume requires that kind of accuracy, but that will be factored in later as part of our O&P in this model.

For a more realistic example, you’re cutting base cabinet sides yielding 6 components, 24” w x 30-1/2” h with some useful drop that’s turned into ladder bases or nailer strips. That’s practically zero waste. With a $ 60/sheet panel, you’re creating 6 components, 5.08 SF per component. $ 9.53 per unit.

Now you have your first unit to estimate from. To accurately estimate this base cabinet you still need your back, top and bottom, drawer front, door, drawer, and legs. After adding all this up though, you'll have a few very useful values:

- The cost of a carcass

- the cost of fronts

- the cost of a drawer box.

I would suggest estimating a 24" base cabinet because it's about as close as we can get to an average base cabinet, plus the yield is good and the math is easy. From this base cabinet, calculate your cubic feet (34.5 x 24 x 24)/1,728= 11.5 cubic feet (cf). Carcasses are estimated by the cubic foot. Now if you want to calculate a unit cost for this assembly method and material, divide your cost by 11.5 to yield your unit cost per cubic foot.

For example, each side costs you $ 9.53 in material, a top and bottom cost you $ 15 in material, the back costs you $ 10 in material, that carcass costs you $ 44.06. You labor inputs cost you 1 labor hour (LH) multiplied by your shop labor rate of $ 40 per hour, then that carcass costs you $ 84.06 bare cost. Divide $ 84.06 by 11.5 cubic feet and your carcass costs $ 7.31 per cubic foot. That's your unit cost. But that's unburdened or bare cost because it is missing two vital pieces of information: your overhead and your profit!

Overhead:

This includes both fixed and variable costs.

- Variable overhead and variable costs fluctuate with the level of production, such as utilities or certain raw materials

- Fixed overhead costs remain relatively constant, irrespective of the production volume, such as property taxes, lease, or insurance.

- This includes your operating costs that are not directly tied to production such as salaries and wages for office and management salaries. Other items, such as depreciation, may appear on COGS, but that will vary by industry.

- Your overhead is added to your subtotal as a percentage called your O&P, or "overhead and profit" which is calculated by:

(annual overhead/12 months)/gross production.

For example, if your shop overhead is $ 48,000/yr, ($ 4,000/mo.), divided by the amount of sales you sell in a year before any expenses are deducted, known as your gross sales. Let's say your gross sales are $ 250,000. Dividing your gross sales by your overhead yields an overhead factor of .192 plus a profit margin of, let's says 30%, 0.30, that give you an O&P factor of .492.

To calculate your sale price from your bare cost with O&P, Multiply your bare cost by 1.492 to yield your sale price. That base cabinet carcass you produced for $ 84.06 needs to sell for $ 125.42 IF and ONLY if you are actually doing the gross sales that you calculated for. If something happens and suddenly you're only doing $ 100,000 in sales, then you need to adjust accordingly. Your business is in big trouble if you have that much overhead and that low of sales, but that would yield an overhead factor of 2.38, meaning you would need to sell that cabinet for $ 200.34. But I could NEVER get that in my market! you may think, then you need to reduce your profit margin. If you're taking a 15% profit, now that's a $ 187.75 cabinet. It's almost like the only way to fix your numbers is to sell, sell, sell and increase your volume...

I recommend keeping with this formula to make it easy to adjust your pricing to meet your sales goals, but that's another topic for another day. I hope this helps!